Once Upon a Time, Bereshit in the Woods

Stories We Tell Ourselves, or Stories We Are Ourselves?

Part One

“Questions of faith and questions of artistic form and content are inseparable.”—Gabriel Josipovici, The Book of God: A Response to the Bible

Let me tell you a story about a storyteller who awoke one morning and asked himself a question: why do I tell stories? The storyteller decided there and then to invent a story that would provide him with the answer.

We have been here before, but how did we get here (again)?

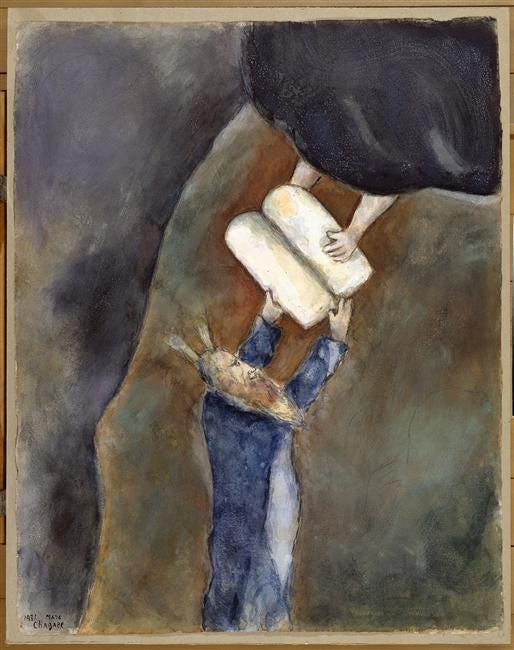

In the beginning (or Once upon a time), God created the heavens and the earth.

As Carlo Suarès rightly comments in The Cipher of Genesis, this proposition, as a literal description of a literal event, is unthinkable:

A “beginning” of time and space is as unthinkable as is their non-beginning. Therefore, a text which proclaims the hopelessly inconceivable leads at the very start into the fictitious domains of wrong thinking. Even the word “God” is inconceivable, obviously so. The hypothesis of the existence of an unthinkable God previous to an unthinkable beginning forces the mind to confront the absurdity of a something before anything creating everything out of nothing (p. 54).

In The Book of God: A Response to the Bible, Gabriel Josipovici’s commentary is more charitable, but compatible with Suarès’ essential point: “the opening words of the Hebrew Bible . . . disorientate us just enough to impose their rhythm on us, but not enough to stop us moving forward” (p. 61).

Bereshit is the Hebrew word that is translated as “in the beginning.” Logically, Bereshit was not the beginning of God, however, only the beginning of a story that God told about Himself to Man; or rather, the beginning of a story men told themselves, about how God told a story about Himself, about how He created the Universe out of Nothing (Himself).

How or why God did this is left open, necessarily. (Who can fathom the mind of God?) Neither is what God was doing before the Creation addressed. The story of Genesis generates its own meaning, its own necessity, because a story about the beginning of “everything” is ipso facto the most important story ever told.

It is also the most impossible to verify. As God asks Job: “Where were you when I created the Universe?” Followed by a version of, “That’s what I thought.”

Without the Creation story, it is implied, there would be nothing to tell stories about and no one to tell them to. We would be hurled back into the abysmal ooze of Norquist’s Haunted Universe, forever, into the primordial chaos of an un-narrativized sequence (or simultaneity) of events.

Every story begins at the beginning because there is no other way to begin a story expect by beginning it. Why do we need stories? To fill the void and keep at bay the horror of incomprehension of the boundless mystery of being? Or simply to pass the time while the food cooks on the fire?

The story I am telling today is, as is so often attempted here, a weaving together of the events, thoughts, influences, and inspirations current in “my life.” They are not so much a story I am telling, as a juxtaposition of other people’s stories (such as those in the Bible) with a critical analysis of them—a quest for meaning—all nested within some seemingly random incidents at the time of writing, which inform the analysis and so turn it into a story (narrative nonfiction, i.e., “my life”).

Yet this is very much the essence of “the story”: the Bereshit in every forest.

Behind the Paywall: “Sabbath of the Year & the Death of Hollywood,” or what I did in the holidays, the good, the bad, & the ugly (The Limey, The Master Gardener, Saltburn, etc.)