A Deep Reading of Why Freud Was Wrong: Sin, Science and Psychoanalysis, by Richard Webster

(Part One Part Two Part Three)

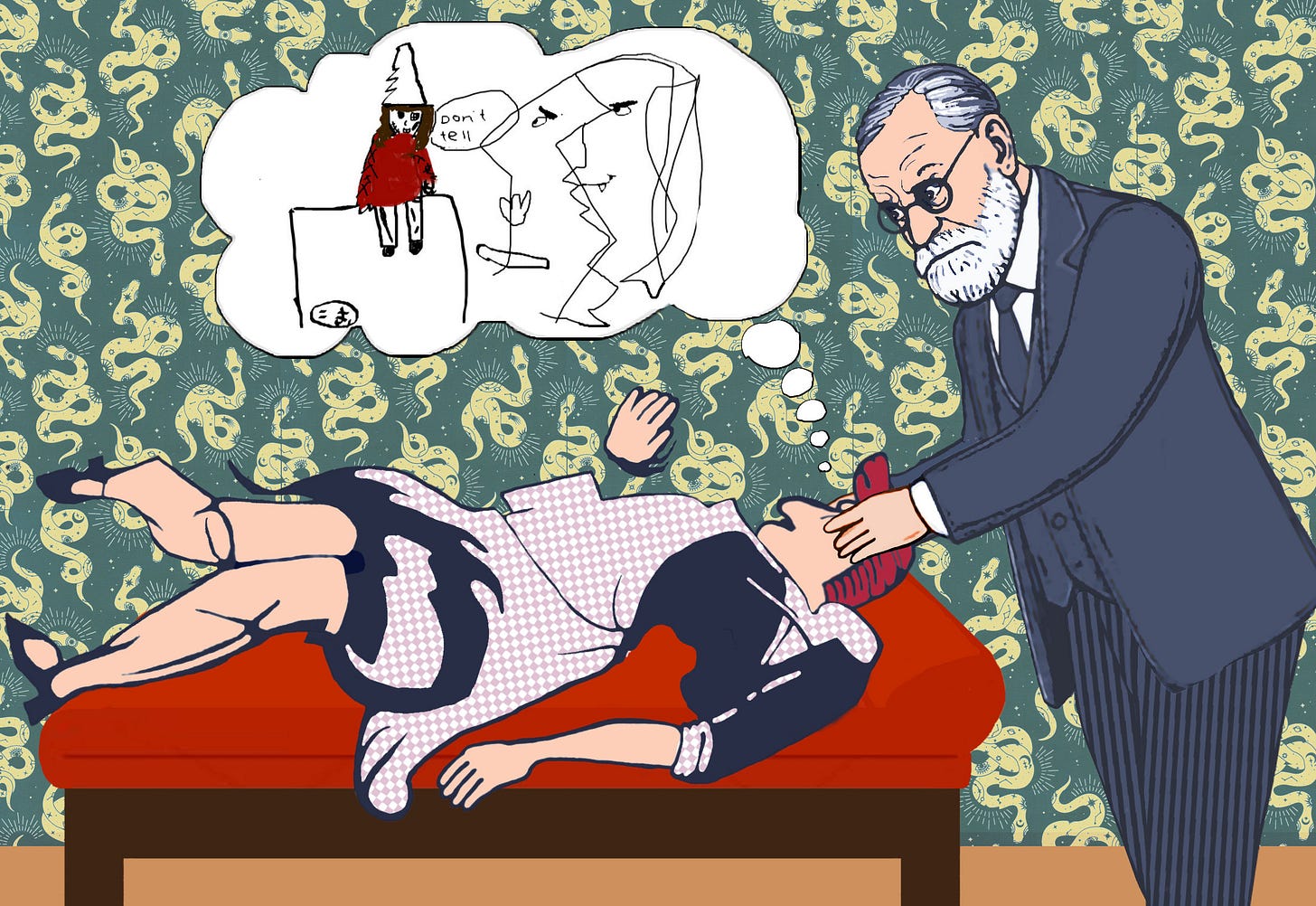

(Art by Michelle Horsley)

More Psychic Sleight of Hand

Previously, we have looked at Webster’s case for Freudian psychoanalysis shifting the diagnostic emphasis from the organic to the psychic, as a means to bring the psychic into the realm of the (pseudo-) scientific. In fact, it’s a more sophisticated and elaborate maneuver, because Freud also held that genuine organic symptoms could be taken over and used by “hysterics.”

What does this mean?

Roughly, this Freudian hypothesis claimed that a patient whose symptoms had been diagnosed as physical could still be treated for hysteria, regardless of whether the original diagnosis was correct or not. The question became, so to say, immaterial, because, Freud claimed that any originary organic symptoms had been “hijacked”—by a sort of psychic organ—and were now being generated psychically, as a sort of ghostly counterfeit of the original disorder.

In a similar manner, if some condition diagnosed as hysteria (i.e., psychic) by Freud—or Breuer or Charcot—was later diagnosed as organic, there was now a retroactive means to argue that, while once organic, it had since become a psychic phenomenon, due to this faculty for turning real symptoms into psychic stigmata! How’s that for masterful sleight of hand?

It might seem that, at least in this case, Freud, by introducing these various modifications into his theories was deliberately and dishonestly taking steps to avoid refutation. Once again, however, to take this view would be to misrepresent Freud’s own attitude. [A]s we have seen, even the death of one of Freud’s patients from a tumor which gave rise to pains which he had judged “hysterical” is not treated as a counter-instance of any kind. Unable to tolerate disconfirmation because he could not live without the sense of fulfillment which his theories brought him, Freud, it would seem, had created a theory which had risen above the very possibility of refutation (p. 151-52).

Elizabeth Von R.

The next case the Webster looks at is that of Elizabeth Von R (Illona Weiss), a young woman who had been experiencing pain in her legs, and who had problems walking for over two years (though she didn’t use a stick). Unsurprisingly, by this point, Freud diagnosed this as hysteria, and wrote that the patient’s pains, though rheumatic in origin, subsequently became “a mnemic symbol of her painful psychical excitations” (p. 160).

Freud suggested a whole series of factors which might have led to this “psychical appropriation.” Rather predictably (with hindsight, that is), Freud offered disappointment in love as the main cause.

Freud reported that Weiss had been nursing a sick father and had been attracted to a young man, but that she couldn’t pursue her interest because of her duty to her father. His theory was that the suppression of erotic desire caused the symptoms, even though there was no obvious psychological correlation between the alleged desire and Weiss’ problem walking or her rheumatic pain. Undaunted, Freud came up with a series of elaborate ideas, including (wait for it) that the patient had either been walking, lying down, or standing at a significant moment in her life. He then included sitting down on his list of possible traumatic scenarios.

It would have been more economical for Freud to have simply stated that the patient had not been running (or floating or standing on her head) whenever the alleged significant event happened. Since Freud decided that any bodily posture at all could be interpreted as relating to the function of the patient’s legs, almost any incident that happened in her life could account for the alleged traumatic imprint, and hence for her problem walking.

Since there is no way to prove or disprove such a diagnosis, it becomes meaningless—but also unfalsifiable.

There are many examples of this sort that Webster cites in his description of Freud’s early years, as he developed his psychoanalytic method (including the interpretation of dreams, a treat yet to come).

Alas—

although Freud has by now launched an entire armada of aetiologies into the sea of speculation with which he has surrounded his patient’s symptoms, he finds himself obliged to confess that her illness has remained unconquered (p. 161).

It was at this time that Freud adopted (from Hyppolyte Bernheim) his technique of pressing his hands on the patient’s forehead and “commanding them to remember,” as a way to squeeze out these traumatic memories, just as if the psyche were a tube of traumata-branded toothpaste.