A Deep Reading of Why Freud Was Wrong: Sin, Science and Psychoanalysis, by Richard Webster

(Art by Michelle Horsley)

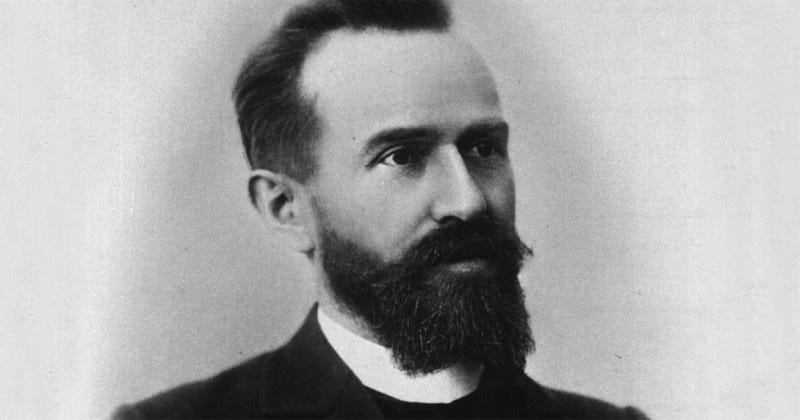

Josef Breuer & Anna O

The next case Webster examines is that of Anna O. (Bertha Pappenheim) and Josef Breuer, the other early mentor that Freud followed, another respected physician with an interest in hysteria. Freud knew Breuer in 1882, before he went to study with Charcot, and he knew about the 21-year-old Anna O.

Anna O. had a plethora of symptoms, including a cough, paralysis, and a tendency to “float” off mentally and not even be aware of what she’d been saying. She suffered from hallucinations, erratic behavior, fits of anger, and eventually lost her ability to speak German and could only speak English, her second language.1

One of the later symptoms that appeared while she was in Breuer’s care was an inability to drink liquids, and Breuer reports that she could only eat fruit in order not to die of thirst. Breuer claimed to cure this latter condition through psychological means, by bringing into her consciousness a memory of being repulsed at seeing a dog drinking out of somebody’s glass. Breuer went on to claim he’d cured all of Anna’s symptoms via similar means, i.e., by accessing memories of traumatic events that had metastasized as “stigmata,” or organic symptoms.

Freud and Breuer wrote a joint paper in 1893 called “Studies in Hysteria,” which introduced a basic model that would become central to psychoanalysis, that of symptoms caused by repressed trauma, and a catharsis-based cure. As Webster has it, a number of such cases formed the diagnostic and therapeutic basis for psychoanalysis, with Anna O. as a central influence.

By presenting the case of Anna O. as a prototype of the cathartic cure, Webster’s argument that Breuer’s claim for this cure was false becomes highly significant. And, as in Charcot’s case of the man who fell from the train, once Anna O.’s real name (Bertha Pappenheim) was discovered, it became possible to look more closely at the facts of the case, and to discover that she hadn’t been cured by Breuer at all. There had been some relief of the symptoms—though even there, Webster says, not a great deal—but they had resurfaced again later.

What’s more, apparently Breuer’s treatment of Anna O. ended because he fell in love with her and had to stop seeing her. So there was certainly no cure; what was worse, by the time the treatment ended she was addicted to morphine. Some years later, Carl Jung questioned Freud and Breuer’s account of the case on this basis, also stating that there was clearly no evidence of a cure.

Conscious Mendacity

Webster takes it further, however, by claiming that even Breuer’s diagnosis was almost certainly wrong. The symptoms that are described, he argues, both by Breuer and in the independent report, are those of temporal lobe epilepsy:

Perhaps the most remarkable feature of the case is not the miraculous cure asserted by psychoanalytic legend—for this cure, as we’ve seen, never took place. It is the misplaced confidence with which Breuer, and after him Freud, completely ruled out the possibility of organic neurological disease without any proper medical grounds for doing so and relied instead on an unproved and unprovable theory of hysteria (p. 121-22).

Webster presents evidence that Breuer not only misdiagnosed Anna O., but that he exaggerated the efficacy of his methods, and covered up evidence that they had failed to cure her. And yet the case went unquestioned by Freud. Did his allegiance to Breuer, combined with his desire to become part of a revolutionary new movement of psychoanalysis, cloud his judgment? Webster suggests a more conscious mendacity at work, i.e., that Freud deliberately covered up the deception so as to benefit from it.

Initially, Freud supported Breuer’s idea of

a miraculous and complete cure . . . brought about by an entirely new method of therapy which was Breuer’s creation. . . . The great advantage of this legend was . . . that it enabled Freud to bask in the reflected light of Breuer’s “miracle,” and thus gain credibility for his own therapeutic strategies, which were closely modeled on Breuer’s pioneering work (p. 134).

Once Freud had achieved his aim, however, and gained recognition as the head of a psychoanalytical movement, he changed his tune. Webster thinks he didn’t want to leave the Breuer legend intact since it would then diminish his own originality in the eyes of his followers: “At both stages of the story, we thus find Freud engaged in the entirely characteristic act of refashioning history in order to suit the needs of his own compulsively messianic identity” (ibid.).