“All that’s really clear is that there is a certain type of human behavior that leans towards the exploitation of others, and another type of behavior that tends towards submission and compliance. Between them, these two tendencies of the human organism and psyche lead to social arrangements that are rife with inequity and injustice. But—and this is the key—the true causative agent in the oppression of humans by other humans remains, to this day, unidentified. Worse, no one seems to be looking for it.” —“The Social Revenge Fantasist: Scapegoating Patriarchy, Generational Trauma, & the Identity Police State”

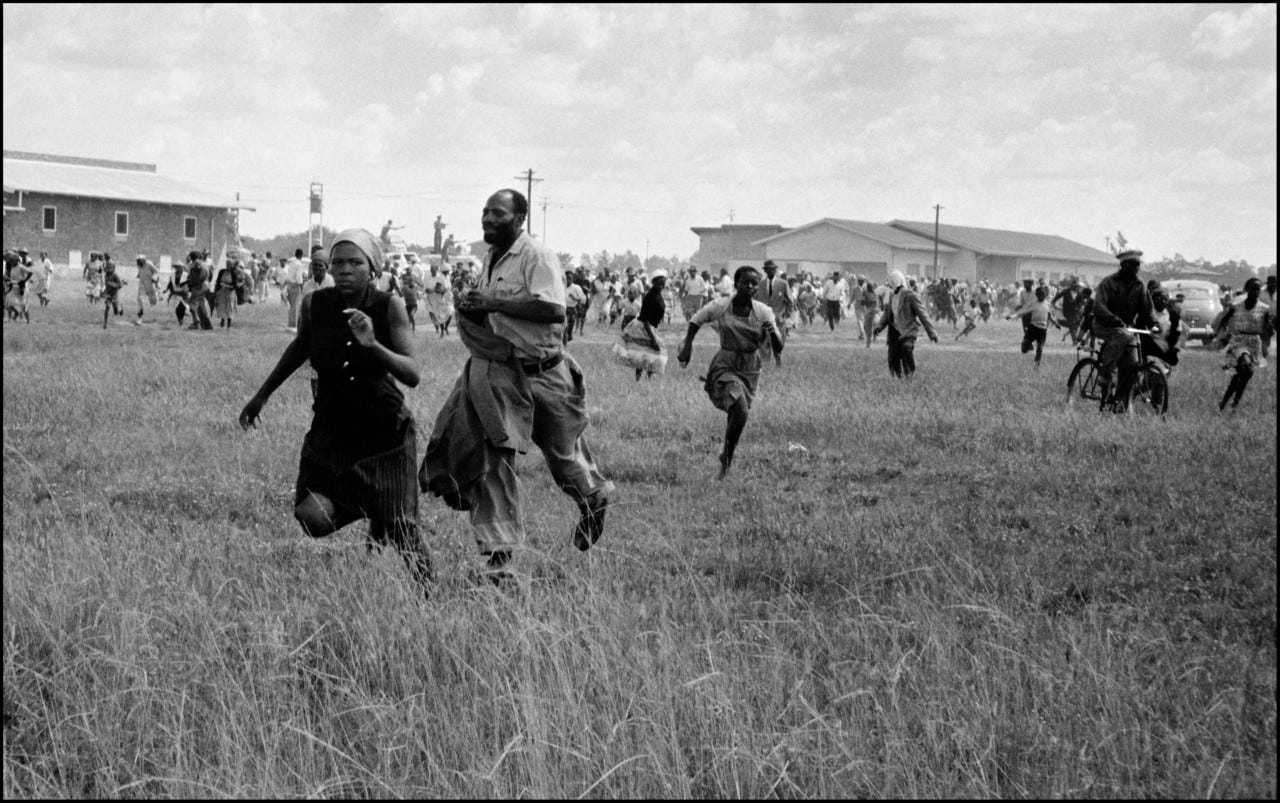

Apartheid, Before & After (the Sharpeville Massacre)

In 1961, Sharpeville was a model South African town, seen as a shining example of the apartheid (racial segregation) regime. The African National Congress (ANC) was the main anti-apartheid group, committed to a multiracial nation. Some activists were disillusioned with the ANC, however, and their policy was “Africa for the Afrikaans,” and an affirmation of racial pride.

The Pan-Africanist Congress, PAC, founded in April 1959, encouraged Black-Nationalism as a way to mobilize the masses. In early 1960, ANC planned a series of protests against laws obliging Africans to carry special identification that authorities could check at any time, thereby restricting where Africans could work, live and travel (sound familiar?). Preempting the ANC’s plan, the PAC launched its own demonstration, on March 21st 1960.

The protest was to proceed in a spirit of “absolute non-violence,” as a way to “provide [the apartheid regime] with an opportunity to demonstrate to the world how brutal they can be” (Robert Sobukwe, PAC president, quoted by De Groot, p. 49).

Similar to the modus operandi of civil rights campaigners in the US, the PAC’s aim was to goad the police into acting violently.

To help ensure this, they cut phone lines into Sharpeville so as to restrict residents’ exposure to less militant influences, and forcibly detained bus drivers in the morning, to prevent residents from leaving for their jobs. People who tried to get to work on bikes or on foot were stopped and threatened by PAC members, and pressured into participating in the protest.

Is it ironic that a demonstration designed to proceed along lines of absolute non-violence used the threat of violence to incite people to participate? Or that it was intended to provoke violence?

Or is this simply page one in the revolutionary playbook?

5,000 protesters assembled and marched to the local police station without passbooks, where they offered themselves up for arrest. The plan was to overfill the jails and bring the local economy to a halt, forcing the government to accept their terms.

When they reached the station, however, the police refused to arrest them. There were around 300 armed police present (a majority brought from outside) and five armored cars, which the police used as platforms to observe the crowd. Low-flying jets were dispatched to scare the crowd away, but the crowd did not budge.

At a certain point, apparently with neither provocation nor warning (though some officers later claimed stones were thrown), the police opened fire on the crowd. In a space of under a minute, 1300+ rounds were fired, 90+ people were killed, including 10+ children, and 238 injured (29 children). A majority of the injured were shot in the back. (These numbers were lower in the original reports and for several decades after, but they were eventually revised.)

While the African government showed no remorse, media coverage of the massacre caused a drastic drop in support for apartheid outside of South Africa, and Britain was forced to chime in with the UN’s condemnation of colonial oppression. Strangely enough, exports to Europe (out-of-season fruit and vegetables and cheap wine) increased, however, which emboldened the African government to ignore the UN’s decree. Instead of relaxing the apartheid restrictions, it tightened them.

In response, the PAC and the ANC formed military wings. Nelson Mandela was chief of staff of the ANC military wing, and in subsequent years, protest groups turned to violence to further their aims (as well as British pop bands).

Since then, the pendulum has swung all the way to the other extreme. Today, South African whites (specifically farmers) are in constant fear of their lives. This is something I heard about directly from someone who lives in South Africa, though an online search for “South African white genocide” brings up two pages of debunking links, including Wikipedia’s “White genocide conspiracy theory” and Snopes, as well some digs against Elon Musk (who was born there). Even Glenn Beck jumped in to cry foul.

It wasn’t until the third page that I found a piece that supports the first-hand testimony I heard from the white South African, called “White Genocide in South Africa: A Holistic Analysis.” Since a sure way to know we are being lied to is by gauging what the algorithms want us to think, I am inclined to credit this analysis as being the more holistic. It also seems to be supported by parallel trends that are observable in other locations.

Revolution Strategies USA

Returning to the early 1960s, and the US civil rights movement, the conventional (and paranoid-oblivious) historian Gerard de Groot writes in The 60s Unplugged that “Nonviolent protest is most successful when it is met by violence, for that is when it becomes newsworthy” (p. 82). DeGroot describes an unusual occurrence in Albany, capital of New York, where “Black activists were comprehensively outmaneuvered by the local chief, Laurie Pritchett. Using informants from within the black community, he anticipated the campaigners’ every move” (ibid.).

Similar to the PAC in South Africa and Gandhi in India, King’s method included filling the jails by non-violent protest. A considerably savvier opponent than usual, Pritchett responded by training his police department into non-violent response. “No violence, no dogs, no show of force. I even took up some of the [activist] training . . . like sitting at the counter and being slapped, spit upon. I said, if they do this, you will not use force. We’re going to out non-violent them.”

By mid-December, more than 500 demonstrators had been arrested, but the campaign had reached a stalemate, thanks mainly to Pritchett. Since the press was unable to produce photos of brutal policemen clubbing protesters, the campaign did not become sufficiently newsworthy to arouse northern sympathies, or provoke the intervention of Attorney General Robert Kennedy. Organizers decided to call in King in order to drum up more publicity (ibid.).

The revolutionary methodology requires violence as the “prerequisite to national awakening,” and so “organizers chose new battlegrounds on the basis of whether the local sheriff could be relied upon to overreact. Protests were carefully stage-managed in order to provoke the most violent response” (DeGroot, p. 89, emphasis added).

Quoting journalist Theodore White:

The police dogs and the fire hoses . . . have become the symbols of the American Negro revolution—as the knout and the Cossacks were symbols of the Russian revolution. When television showed dogs snapping at human beings, when the fire hoses thrashed and flailed at the women and children, whipping up skirts and pounding up bodies . . . the entire nation winced as the demonstrators winced (p. 89).

The revolutionary playbook shows that, to beat the system, you must join the system. It requires playing by its rules and learning its language. This raises the question, at the end of that game: Cui bono?

Christ’s disciples were scandalized by their leader’s policy of nonresistance, since it more or ensured that their new movement die in its manger—or so they thought. (In fact, it died on the cross, and the cross became the movement.)

Revolutionary movements (like evil) thrive on resistance. It is in their interests for the regime they are opposing to become, not less but more oppressive, to show its “true colors.” So what does that indicate about the true colors of the revolution?

Pritchett’s strategy might have been designed to beat King at his own game, or merely an attempt to maintain order in his town. The salient point is that it was non-violent, and it worked. By meeting non-violence with non-violence Pritchett avoided an outbreak of violence in Albany.

This was not what the civil rights activists needed to achieve their goals, however.

(Pritchett said in 1976 that he had considered MLK a “close personal friend.”)

Endless Revolt

Revolution doesn’t want incremental change but catastrophic change. And revolution, as the word suggests, is a never-ending process, since resistance reinforces that which is being resisted.

Something I wrote in 2020:

The horrors and injustices of “history” (itself a necessarily fictional construct) are a matter of opportunity and of scapegoating. Where there is an opportunity to oppress and exploit, it is taken. The degree of successful exploitation determines the divide between strong and weak, oppressors and oppressed, rich and poor. Because of generational trauma, unhealed wounds, ancient vendettas, given the opportunity and the means, any race, sex, or class will tend to oppress another, and so become the dominator group. If we don’t find evidence of this, either we aren’t looking hard enough or the “history” we are examining hasn’t been documented thoroughly enough.

Insofar as the revolutionary method aims to bring about the very abuses of power it is supposedly trying to prevent, any oppositional movement becomes complicit with the regime it opposes.

The end justifies the means, we are told; but if nonviolence is a strategic means to achieve worldly power, and if it involves provoking violence in the enemy, how is that different from the direct use of violence for these same ends?

As the above examples suggest, this sort of studied and strategic use of non-violence is complementary with violence. This presents a maddening conundrum that is fully confirmed, in all its vicious circularity, when the seemingly oppressed groups, in the process of “freeing” themselves from oppression, themselves become oppressors.

There seem to be no end to cases of this, whether it is South Africa, Israel, or the US with its racial “reparations,” by which whites are forced to allow blacks to take over their homes, for the sake of righting an ancestral injustice.1 When correcting present circumstances is no longer enough, and the past must also be amended and paid for, there is no end to the revolution.

“Justice” becomes revenge, retroactive, retaliatory, and circular.

The demand for racial justice, sexual equality, etc., is like a voracious hunger that grows the more it feeds. Its demands become not more but less reasonable, the more they are met.

Black Power becomes Black Privilege and a punishment of Whiteness; the exact same abuses are replicated in mirrored form, and the balance of racism shifts on its axis. Racism then becomes a rational response to reality, so-called “white supremacy” no longer an offensive but a defensive position, a matter not of persecution but of preservation.

Currently, we are told, there is a kind of an “anti-revolution” revolution in which “deep state” heads are rolling in the US, following Donad Trump’s inauguration. As the pendulum swings back (as I predicted it would last year), Team-Trump, the spearhead for the “new right,” ushers in the promised return to conservative, traditional policies that will make America great again.

But behind the curtain (and not even well-concealed), the same long-term goals are unfolding, using both left and right forms of revolutionary change, with the fulcrum of conservativism and populism to stabilize the right-left seesaw of sustained destabilization.

By this method, societies (as well as human bodies and psyches) are incrementally reconfigured, at ever-accelerating rates of progress.2

House Wins

“The most successful revolution of the 1960s was not conducted by students, nor was it left-wing. It was instead a populist revolution from the right, which had Ronald Reagan as its standard bearer.” —Gerard de Groot, The 60s Unplugged (p. 406).

As Yoshi (“Holy Is He Who Wrestles”) wrote this week about a hypothetical, advanced, nonhuman species manipulating things behind the scenes (with DJT’s $500 billion AI Stargate as the ingress window and landing pad): “Assume whatever effect they’re having is the goal.”

If DJT is bringing about revolutionary change in US policies, you can be sure that’s because Uncle Screwtape requires them as the latest phase in his long-term strategy.

Think about it.

Leftist liberal-progressivism was the thrust of cultural revolution in the 1960s. It seemed at the time to be unequivocally necessary, good, and right, and that’s how it looked with the hindsight of a couple of decades—itself the proof of a “successful” revolution (when the values propounded become dominant).

In 2025, the thrust of the US revolution is rightist conservatism and populist traditionalism. To many, this too seems necessary, good, and right, as a counter-measure to the “woke” takeover that was both cunningly and naively associated with the “Deep State” Establishment.

Just as if multi-generational social engineers had ideological allegiances . . .

In between the 60s and now, the 80s and 90s saw the rise of neoliberalism and an apparent swing in the opposite direction, even while the values of civil rights and sexual “liberation” were taken as given. The noughties and the 2010s saw the rise of “Woke,” as the second wave of the sixties, and bigotry, racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, right-wing extremism, anti-semitism, etc., again became enemy # 1.

Just as they were in the 1960s.

Just as if nothing had changed.

Because it hasn’t.

Now the so-called rise of the new right—which also happened in the 80s—is being seen as an “organic” response to that.

The more things change, the more they stay same—because it doesn’t matter how many times the wheel spins, or where it stops (or seems to stop) at any given time. The axis never moves.

Is such an overview, broad and simplistic as it may be, sufficient to dash all hopes that the latest spin of the roulette wheel will benefit anyone but the House?

Were reason or common sense in the driving seats, it might indeed be so. But it isn’t, and it hasn’t been for a long time.

Today, the political true believer—even the supposedly paranoid-aware one—seems really no different from the compulsive gambler for whom losing is every bit as addictive as winning.

It’s tautologous to say that no one achieves worldly power without a hunger for power. And the hunger for power—which is always justified by noble intentions—is what keeps the lazy-Susan of global politics turning.

Isn’t it safe to assume, therefore, that all visible human agents of change are merely hors d’oeuvre in a hyper-dimensional game?

And that revolution is the Devil’s Smorgasbord?

And let me know what you think:

Armed Activists Seized Three Blocks of a North Portland Residential Neighborhood.

‘GIVE UP YOUR HOUSE’ Black Lives Matter activists storm neighborhood and demand white residents give up their homes.

No evictions ever law:

Communist’ group leading ‘good cause’ eviction debate in Albany.

The Fabian-founded London School of Economics, in the words of DeGroot, was “the unofficial headquarters of the British New Left,” and the main locus of student revolt in the UK in the 1960s. “In addition, the university had a rather strange tradition of hiring reactionary administrators who reveled in righteous authority” (p. 356). But is it so strange, if such a policy could serve as one way to ensure LSE students were constantly revolting? Much stranger is the fact, as discussed in The Vice of Kings, that The Rolling Stones began as an LSE project.

Well crafted post Jasun, very interesting about how non violent resistance is violent. Food for thought. Indeed the seesaw/pendulum swings. I’d be interested to know your thoughts about when the axis or fulcrum breaks, how many revolutions, how many cycles.

I have been reading Screwtape for the first time this month. So timely reference for me.

"Pritchett’s strategy might have been designed to beat King at his own game, or merely an attempt to maintain order in his town". Pritchett was doing his job.

It seems to be a human need to wake up in the morning and think what shall I do today? A paid job is the current way but that payment will change for most, judging by Agenda 2021.

Whether they really want a Gaia-type world for the sake of humanity, or because a cybernetic, self- regulating sysytem is so much easier to manage than one requring armies, is a question. I find it difficult to give them the benefit of the doubt judging by the harm done by trans national events in this and the last century.

They rely on us doing our jobs. If we were to give up on modern technology for a while it might allow us to break free from their grip. Ted Kaczynski had an IQ of 167. Nuff said. Being in control of your day is good for the body and mind. That will only happen if it is offered as a choice and many would choose it. We are not beyond hope as that wouldn't be natural or human.

Given a chance, it does appear that the oppressed will oppress but I kind of think some of this division (Trump/Biden etc) and suppression of white people, is being engineered by those in control of the game we are playing. Left to our own devices, maybe we could live peacefully in our own worlds. I have every faith in my fellow humans who are not influenced by propaganda.