A Deep Reading of Why Freud Was Wrong: Sin, Science and Psychoanalysis, by Richard Webster

(Part One · Part Two · Part Three · Part Four)

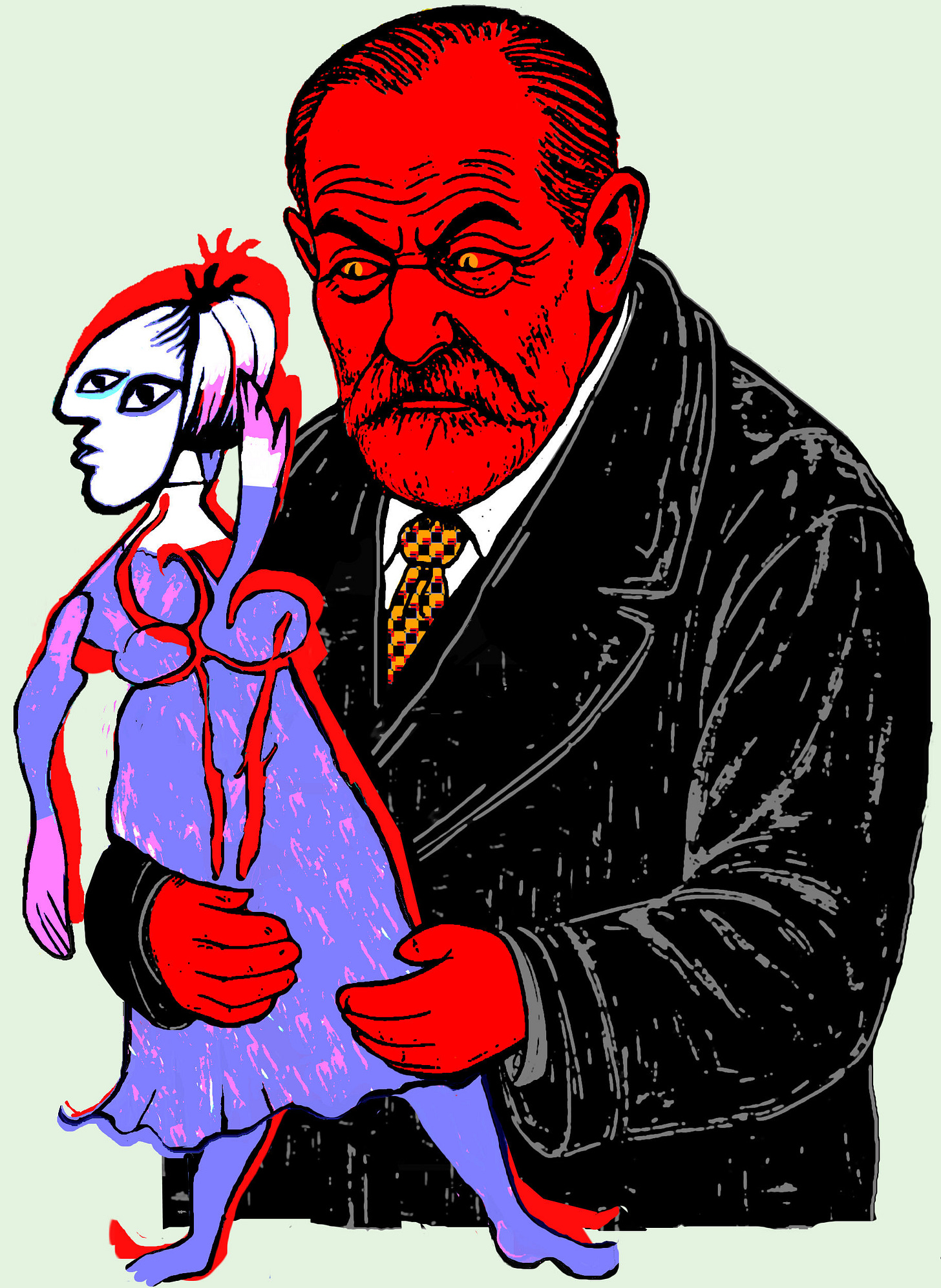

(Art by Michelle Horsley)

Aetiological Monotheism

“Freud had decided . . . that the inner workings of the unconscious were ultimately more important than events in the real world, and that when it came to constructing psychological theories, the latter should sometimes be disregarded in favor of the former” (Webster, p. 215).

To reiterate: Freud’s methodology, as described in previous sections, was guaranteed to always find confirmation.

Freud would adjust his theory, not in order to accommodate facts, but in order to obscure facts and/or render them irrelevant. If a story the patient recounted didn’t bring about improvement in their condition, Freud considered their story incomplete. If the patient assured Dr. Freud they weren’t concealing anything from him, as a matter of principle Freud never accepted their claim:

We must not believe what they say. We must always assume, and tell them too, that they have kept something back because they thought it unimportant or found it distressing. We must insist on this. We must repeat the pressure and represent ourselves as infallible, till at least we are really told something (p. 197, emphasis added).

Webster recounts one case of a patient claiming her anxiety attacks began after applying iodine to a swollen thyroid gland. Freud wrote: “I naturally rejected this derivation . . . and tried to find another instead of it which would harmonize better with my views on the aetiology of the neuroses” (ibid., Webster’s italics). Freud even candidly admits that he would often lead his patient’s attention to “repressed sexual ideas in spite of all their protestations” (ibid., Webster’s italics).

Freud, in short, treated his patients as suspects, to be ruthlessly interrogated to extract a confession. If he couldn’t get a confession, Webster stresses, he would write one for them, and then have them sign it. If Freud couldn’t get them to sign the confession he wrote for them, he would sign it for them as well—all of this regardless of whether or not they were actually guilty, and whether or not it provided them with any cure.

The idea of Freud as a police inspector is far removed from the image which tends to be projected onto the founder of psychoanalysis by most of his followers. [And yet], in a very significant number of other cases, Freud’s attitude is strikingly similar to that of a policeman (p. 199).

Perhaps an even closer analogy would be that of a prosecutor; and the prosecutor-accuser is the meaning, and function, of hassatan, the Satan. Webster’s Freud was even worse than this, however, framing the suspects, Gestapo-like, by writing their “confessions” and signing them in their name. In Webster’s view, this method

undoubtedly grew not out of any essential dishonesty, but out of Freud’s burning zeal both to substantiate his own theories and to effect a cure, [making it] crucial to the understanding of psychoanalysis as a whole. . . . Freud’s tendency to engage in single factor analysis of any specific phenomenon he was studying was clearly an essential part of his scientific temperament. It was a kind of aetiological monotheism. This tendency was strongly reinforced by his medical training. (p. 200-201, emphasis added).

Leading the Witness

In order for Freud’s therapeutic model to be confirmed, and to prove consistent, his cathartic cure could only work if a repressed memory was brought to light via the psychoanalytical method. This meant that, if a patient recounted an instance of sexual seduction or molestation spontaneously, it had to be discounted as a pathological factor, seeing as how it had not been suppressed.

Freud would therefore ignore any sexual traumas recounted by patients who were already aware of what had happened to them, since he was looking for memories buried deep in the past, in early childhood, before memories were formed.

Freud’s “therapeutic rule” was that analysis is not completed until some sort of memory has been recovered—or (re)constructed—by the therapist, on the basis of the patient’s associations. This was what Freud was constantly doing: spinning stories out of clues the patients were giving him, without their realizing their significance.

The psychoanalytical patient is only able to give inadvertent indications of the issue, then, which the psychoanalyst must piece together and then present to the patient as a diagnosis.

Yet Freud’s methods, as described by Webster, would be seen by any decent therapist today as appalling, and as totally unethical. So it would be a mistake to think that this particular aspect has prevailed in psychoanalysis, despite claims about “satanic panics” and false memories. Nonetheless, the fact remains that this method was present at the very foundation of psychoanalysis, and so can hardly have failed to have caused untold amounts of confusion and malpractice.

It is extremely significant, therefore, that Freud was basically imposing a therapeutic model onto his patients, and illegitimately asserting its efficacy. He had no bones about telling his patients what kind of memories they were supposed to be uncovering, as a means to “help” them to recover them. By his own account:

They are indignant as a rule if we warn them that such scenes are going to emerge. Only the strongest compulsion of the treatment can induce them to embark on the reproduction of them. . . . Only the most laborious and detailed investigations have converted me, and that slowly enough, to the view I hold today. If you submit my assertion that the aetiology of hysteria lies in sexual life to the strictest examination, you’ll find that it is supported by the fact that, in some eighteen cases of hysteria, I’ve been able to discover this connection in every single symptom, and where circumstances allowed to confirm it by therapeutic success (p. 203, 206).