A Deep Reading of Why Freud Was Wrong: Sin, Science and Psychoanalysis, by Richard Webster

(Part One · Part Two · Part Three · Part Four · Part Five · Part Six · Part Seven · Part Eight)

(Art by Michelle Horsley)

The Heretics

Many of the criticisms Webster levels at Freud in the first part of his book were actually leveled at Freud during his lifetime, including by Freud’s followers. Albert Moll, for example, a highly respected “sexologist”:

The impression produced in my mind is that the theory of Freud and his followers suffices to account for the clinical histories, not that the clinical history sufficed to prove the truth of the theory. Freud endeavors to establish his theory by the aid of psychoanalysis, but this involves so many arbitrary interpretations that it is impossible to speak of proof in any strict sense of the term (p. 358).

As Webster recounts it, Freud attacked Moll face to face for his misgivings, insulted him and verbally abused him—a pattern that runs throughout Freud’s relationships.

In the Church of Freud, any who question or disagree with the Messiah—even those who dare to branch out and develop their own ideas—are cut down to size by Herr Freud without mercy. The first apostate to receive the treatment was Alfred Adler, whom Freud named a heretic for suggesting that power was more prevalent in human psychology than sexuality, and more central to understanding it.

Freud attacked Adler without mercy, and Adler was banished into the wilderness like the proverbial scapegoat. (Wilhelm Stekel was ejected along with Adler for backing up Adler’s theory.) Webster quotes witness Max Graff:

if one followed Adler and dropped the sexual basis of psychic life, [Freud insisted] one was no more a Freudian. In short, Freud, as head of the church, banished Adler; he ejected him from the official church. Within the space of a few years, I lived through the whole development of church history; from the first sermons to a small group of apostles, to the strife between Arius and Athanasius (p. 362).

Webster’s Leap of Hubris (Jesus’s “Messiah Complex”)

That “psychoanalysis . . . is quintessentially a religion and should be treated as such” (p. 362) is very much the spine of Webster’s anti-Freudian thesis. For Webster, the problem is not so much that Freudianity is a pseudo-religion, however, but that religion, in any form, is a grand folly.

It is here that the book’s central fallacy becomes explicit. Webster’s rejection of religion, of Judaeo-Christianity specifically, goes so far as to frame Jesus—as a historical figure—in the same terms as Freud, along with anyone else he diagnoses as suffering from a neurotic messianic complex. Needless to say this is a Promethean—and entirely unnecessary—leap of hubris.

Webster even uses the Gospel as evidence for how this pattern can be observed throughout history. Jesus is another crackpot who believes God has chosen him and who seeks out followers from a sense of duty driven by a fear of divine punishment.

The idea that Jesus—or the other prophets—might be moved by the joyous impulse to share the Holy Spirit with others, seeking those with ears to hear as a means to spread it further, this is a possibility Webster does not—perhaps cannot—consider. It is all just atavistic gobbledygook, roundly disproven by Darwin.

Webster writes, “ultimately, however, since the God he worships is purely imaginary, there’s no way in which he can be reassured about his own sense of election” (p. 363, emphasis added). It is at this point that Webster tips his hand and reveals a didactic arrogance that threatens to eclipse Freud’s own. To state emphatically, without qualification or any attempt to back it up with evidence, or even argumentation, that God is imaginary and that Christ was deluded and could only affirm that delusion by luring followers into it, shows how deeply entrenched Webster is in his reductionist mindset.

Ironically, all Webster’s many insights about Freud have emerged from a blinkered consciousness so committed to articles of faith (such as that God has been proven by Darwin not to exist) that he winds up drowning in the same black swamp he abhors Freud for.

He abandons scientific rationalism to prove a pet theory.

Crown Prince, Beloved Son

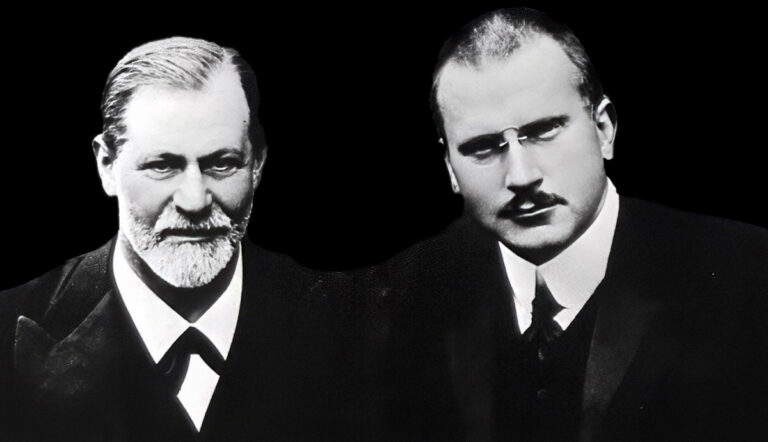

Jung and Freud first met in 1906, when Jung was 31 or 32 and Freud was 50. Jung sent Freud a copy of a book he had written about word association tests, and they both fell swiftly into a worshipful relationship.

Obviously, it was Jung who worshiped Freud at first; but Webster describes the relationship as quite reciprocal: Freud favored Jung as a chosen disciple, and in 1910 selected him as the head cornerstone of his new religion. He began to count on Jung to continue his legacy, and even chose him to be the public face of psychoanalysis (because Jung was a gentile).

In these early years, Freud was grooming Jung to this very end: “If I am Moses, he wrote to Jung in 1909, then you are Joshua and will take possession of the promised land of psychiatry, which I shall only be able to glimpse from afar” (p. 372).

Despite the envy of the other disciples, the relationship continued in this manner for about three years. The turning point came when they were traveling in the US in 1909. Jung was interpreting a dream of Freud’s, the content of which seemed to refer to Freud’s sexual affair with his wife’s youngest sister. Freud didn’t know Jung knew about the affair, and when Jung asked Freud about any personal associations he might have with the dream, Freud “looked at [Jung] with bitterness and said, ‘I could tell you more, but I cannot risk my authority.’”

This was the turning point for Jung. To Jung, Freud was putting his own ego, his own defenses, before the quest for truth. It was the beginning of the end of their idealized collaboration, an end which Jung saw before Freud.